|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Norman Foster

[Norman Robert Foster] |

|

* Manchester (England), United Kingdom, 1 June 1935 |

| nationality:

british |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Riverside, 22 Hester Road |

|

SW11 4AN London -

United Kingdom |

|

Tel: +44.20.7738.0455

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hamdan Street, Office 302, Level 3, Al Saman Tower B

P.O Box 45715 |

|

Abu Dhabi -

United Arab Emirates [Al-Imarat al-'Arabiya al Muttahida] |

|

Tel: +971.2.417.1700

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3707, SOHO Nexus Centre, 19A East 3rd-Ring Road

Chao Yang District |

|

100020 Beijing -

China [Zhōngguó/Zhōnghuá] |

|

Tel: +86.10.5705.3000

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 Infinite Loop, MS:21-3AC2 |

|

95014 Cupertino [CA] -

United States |

|

Tel: +1.408.610.5800

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Office 110 Building 8

Dubai Design District |

|

Dubai -

United Arab Emirates [Al-Imarat al-'Arabiya al Muttahida] |

|

Tel: +971.4430.6656

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3001 Tower 2 Lippo Centre, 89 Queensway |

|

Hong Kong [Xianggang] -

China [Zhōngguó/Zhōnghuá] |

|

Tel: +852.29896288

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| c/ Monte Esquinza 48 |

|

28010 Madrid -

Spain [España] |

|

Tel: +34.91.310.7820

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 300 West 57th Street, 26th Floor |

|

10019 New York [NY] -

United States |

|

Tel: +1.212.641.9600

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1000 Sansome Street, Suite 240 |

|

94111 San Francisco [CA] -

United States |

|

Tel: +1.408.610.5800

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5F, JiuShi Building No.28, Zhongshan South Road

Huangpu |

|

200010 Shanghai -

China [Zhōngguó/Zhōnghuá] |

|

Tel: +86.021.5368.3888

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AWARDS |

|

|  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

American Prize for Design

Good Design Awards

The Chicago Athenaeum: Museum of Architecture and Design

The European Centre for Architecture Art Design and Urban Studies

|

|

|

|

|

Twenty Years of Excellence Award

AJ Architects Journal |

|

|

|

|

Louis Kahn Memorial Award

Philadelphia Center for Architecture and Design |

|

|

|

|

Save the Children Award

Save the Children Spain |

|

|

|

|

| Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Artes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China Friendship Award

Peoples Republic of China

State Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs |

|

|

|

|

Praemium Imperiale

Architecture

Japan Art Association |

|

|

|

|

| Pritzker Architecture Prize |

|

|

|

|

| Title of Lord Foster by Thames Bank |

|

|

|

|

| Order of Merit by the Queen |

|

|

|

|

Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters

Ministry of Culture, France |

|

|

|

|

AIA Gold Medal

The American Institute of Architects |

|

|

|

|

Gold Medal

French Academy of Architecture |

|

|

|

|

Royal Gold Medal

RIBA - Royal Institute of British Architects |

|

|

|

|

BUILDINGS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China [Zhōngguó/Zhōnghuá]

China [Zhōngguó/Zhōnghuá]

» Beijing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United States

United States

» New York - Manhattan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spain [España]

Spain [España]

» Bilbao (Bilbo) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malaysia

Malaysia

» Bandar Seri Iskandar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Gateshead |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

France [France]

France [France]

» Quinson |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Germany [Deutschland]

Germany [Deutschland]

» Hamburg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Sunninghill and Ascot |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China [Zhōngguó/Zhōnghuá]

China [Zhōngguó/Zhōnghuá]

» Hong Kong [Xianggang] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spain [España]

Spain [España]

» Valencia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Duxford |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Cambridge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Stansted Mountfitchet |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spain [España]

Spain [España]

» Barcelona |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Norwich |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» London |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Cosham |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Swindon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Ipswich |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Swindon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Feock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

» Radlett |

|

|

|

|

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WRITINGS

BY THE ARCHITECT |

|

|

|

|

| Norman Foster, "Masdar City e il nuovo Masdar Institute Campus ad Abu Dhabi/Masdar City and the Masdar Institute Campus, Abu Dhabi", L'industria delle costruzioni 419, maggio-giugno/may-june 2011 [Ecocities], pp. 26-35 |

|

|

| Luis Fernandez-Galiano, Norman Foster, (ed.), Buckminster Fuller 1895-1983 [AV Monograph 143], Arquitectura Viva, Madrid 2010 |

|

|

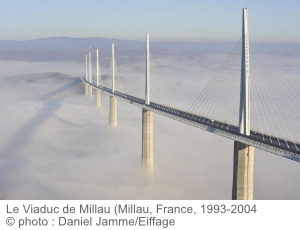

| Foster and Partners, "Il viadotto di Millau" in Alessio Pipinato (ed.), EdA esempi di Architettura 2, 2/2007 [Corridoio V. L'evoluzione nella progettazione delle infrastrutture], "Corridoio V. Gomma: Buone pratiche" pp. 52-53 |

|

|

| Foster & Partners, ADFEC, "UAE: The future now. The world's first carbon-free city", A+. Architecture Plus. Architecture of a New World 16, 2007, "Context. Community & Planning" pp. 104-105 |

|

|

Norman Foster, Reflections, Prestel, 2005 Norman Foster, Reflections, Prestel, 2005 |

|

|

Norman Foster, Catalogue. Foster and Partners, Prestel, 2005 Norman Foster, Catalogue. Foster and Partners, Prestel, 2005 |

|

|

| Norman Foster, "Il bacio delle torri: Norman Foster/The kissing towers", Domus 856, febbraio/february 2003, "Servizi/Features" pp. 44-45 (32-49) |

|

|

"La torre e la città/The tower and the city", Domus 840, settembre/september 2001, "Servizi/Features" pp. 36-101

Norman Foster, "Il grattacielo 'responsabile'/The responsible skyscraper", Domus 840, settembre/september 2001, "Servizi/Features" pp. 52-57 (36-101) |

|

|

| Norman Foster, "British Museum, Londres/Great Court, British Museum, London", Arquitectura Viva 77, III-IV 2001 [Mil Museos], "Arquitectura" pp. 40-45 |

|

|

| Norman Foster, "Foster Associates. Carré d'Art, Nîmes", GA Document 37, september 1993, pp. 36-49 |

|

|

| Norman Foster, "Botany 2000. The National Botanic Garden of Wales, Middleton Hall", Landscape Design 270, may 1988 [Millennium projects review], pp. 48-51 |

|

|

| Norman Foster, Three Themes, six projects, Electa, Milano 1988 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

WRITINGS

ABOUT THE ARCHITECT |

|

|

|

|

Frédéric Migayrou (ed.), Norman Foster, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, Paris 2023 (exhibition’s catalogue) |

|

|

Jean-Marc Prévost,  Moving. Norman Foster on Art, Ivorypress, 2013 Moving. Norman Foster on Art, Ivorypress, 2013 |

|

|

David Jenkins, Catalogue. Foster + Partners, Prestel Verlag, 2008 David Jenkins, Catalogue. Foster + Partners, Prestel Verlag, 2008 |

|

|

| Edoardo Piccoli, "Il superarchitetto che piace ai manager", Il giornale dell'architettura 52, giugno 2007, p. 9 |

|

|

| Philip Jodidio, UK: Architecture in the United Kingdom, Taschen, Köln 2006, p. 107 (107-123) |

|

|

Norman Foster, Catalogue. Foster and Partners, Prestel, 2005 Norman Foster, Catalogue. Foster and Partners, Prestel, 2005 |

|

|

| Valentina Croci, "Nuovi scenari ecosostenibili/New Eco-Sustainable Scenarios", Ottagono 167, febbraio/february 2004, pp. 140-153 |

|

|

| Deyan Sudjic, "Norman Foster al varco di Ground Zero/Waiting in the wings: Norman Foster and Ground Zero", Domus 856, febbraio/february 2003, "Post Script - Ripensamenti/Reputations" pp. 138-139 |

|

|

| David Jenkins, Hashim Sarkis, Norman Foster. Works 1, Prestel USA, 2003 |

|

|

| Philip Jodidio, Architecture Now!, Taschen, Köln 2001, pp. 94-99 |

|

|

| Giuseppe Zampieri, "Foster in Gran Bretagna/Foster in Britain", Domus 825, aprile/april 2000, "Itinerario/Itinerary 166" pp. 120-128 |

|

|

| Philip Jodidio, Building a new millennium, Taschen, Köln 2000, pp. 164-165 (164-175) |

|

|

| Mario Antonio Arnaboldi, "Il Premio Pritzker/To Sir Norman Foster", L'Arca 139, luglio-agosto/july-august 1999 [Strutture/Structures], "l'Arca2" p. 98 |

|

|

| GA Document Extra 12, 1999 [Norman Foster] |

|

|

Martin Pawley, Norman Foster. A Global Architecture, Thames & Hudson, London 1999

tr. it.: Norman Foster. Architettura Globale, Rizzoli, 1999 |

|

|

| Daniel Treibler, Norman Foster, E & FN Spon, London 1992 |

|

|

| Ian Lambot (ed.), Norman Foster. Team Four and Foster Associates. Buildings and Projects 1964-1973. Volume I, Watermark Publications, 1991 |

|

|

| Ian Lambot (ed.), Norman Foster. Foster Associates. Buildings and Projects 1971-1978. Volume 2, Watermark Publications, 1990 |

|

|

| Ian Lambot (ed.), Norman Foster. Foster Associates. Buildings and Projects 1978-1985. Volume 3, Watermark Publications, 1990 |

|

|

| Aldo Benedetti, Norman Foster, Zanichelli, Milano 1988 |

|

|

| François Chaslin, Frédérique Hervet, Armelle Lavalou, Norman Foster, Electa Moniteur, 1986 |

|

|

|

|

|

THE ARCHITECT IN CINEMA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Title |

|

|

|

| How much does your building weigh, Mr. Foster? |

|

| Directed by |

|

|

|

| Norberto Lopez Amado, Carlos Carcas |

|

| Nationality |

|

|

|

|

| Year of production |

|

|

|

|

| Cast |

|

|

|

| Norman Foster, Tony Hunt, George Weidenfeld, Richard Rogers, Bono, Deyan Sudjic, Paul Goldberger, Carl Abbott, Alain de Botton, Anish Kapoor, Richard Serra, Anthony Caro, Richard Long, Buckminster Fuller, Ben Cowd, Cai Guo-Qiang, Ricky Burdett, Spencer de Grey, David Nelson, Narinder Sagoo, Nigel Dancey, Loretta Law, Mouzhan Madidi, Stefan Behling, Jurgen Happ, Gerard Evenden

|

|

| Architect's role |

|

|

|

Protagonist

Tracing Lord Foster’s career, from his childhood in Manchester to the global practice that he founded and chairs, the documentary looks at his architecture, why it matters and how difficult it is to do well. The film uses cinematography to capture the spectacular scale of projects such as the Millau Viaduct, Beijing Airport and Swiss Re, on the big screen for the first time. Tracing Lord Foster’s career, from his childhood in Manchester to the global practice that he founded and chairs, the documentary looks at his architecture, why it matters and how difficult it is to do well. The film uses cinematography to capture the spectacular scale of projects such as the Millau Viaduct, Beijing Airport and Swiss Re, on the big screen for the first time.

Stills gallery Stills gallery |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

INTERVIEWS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interview by Frédéric Migayrou with Norman Foster Interview by Frédéric Migayrou with Norman Foster

Read the full interview in: Frédéric Migayrou (ed.), Norman Foster, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, Paris 2023

catalogue of the exhibition: Norman Foster, Paris [France], Centre Pompidou (Galerie 1, level 6), 10 may / 7 august 2023

Frédéric Migayrou: Norman Foster, you have worked on many types of programs, including airports, transportation systems, museums and universities, and for each of them, the question of locality is always present. What is the relationship between the global vision of the architecture you develop, and the specificity of each project’s context?

Norman Foster: Trends are global in cities. For example, the relationship between mobility and public space – whether it’s Seoul, Boston, or Madrid – the trends we are witnessing are the same. We are seeing road systems being either partly buried or diverted, and more space given over to people and nature. But what happens on the ground relates to the particular place; every city is different. It’s the same with an individual building. It has components which come from all over the world, but the way they come together responds to a specific brief. The challenge is to maximise the differences, rather than encouraging homogeneity. The answer is to encourage local DNA and culture, to be sensitive to them, and to have the best of both worlds. In short, each project should be of its place.

FM : How did this vision of architectural and urban complexity first take shape? You often mention your discovery of the technical complexities of locomotives and aircraft at a young age through drawings in Eagle magazine, and also your exposure to Manchester’s architecture, for instance the Barton Arcade and Alfred Waterhouse’s Town Hall, or Owen Williams’s Daily Express Building. How was your original understanding of architecture arrived at?

NF : As a child, I was drawn to magazines and books which showed the cutting-edge technologies of the time, with drawings that revealed their inner components. When I made my first drawings at the Manchester School of Architecture, I chose not to restrict myself to just plans, sections and elevations, which are two-dimensional. I was also taking those buildings apart, seeing how they work and drawing them three-dimensionally. While my drawings have become more sophisticated, they still seek to explain the inner workings and systems of a building...

FM : After receiving your master’s degree, you obtained a scholarship to study at Yale University in the United States, where you met Richard Rogers. The influence of architects such as Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph and Serge Chermayeff was to prove decisive, as was your discovery during a trip to California of new construction principles at the Case Study Houses designed by Craig Ellwood and by Charles and Ray Eames, and also in Ezra Ehrenkrantz’s School Construction Systems Development (SCSD).

NF: I think influences can either be conscious or subconscious – and we’re all a product of them. If I think about my first experience of going into the School of Architecture, which was located in the Louis Kahn Building at Yale University Art Gallery, I recall the famous picture of Kahn looking up at the diagrid ceiling. That ceiling could never have happened without the pioneering work of Richard Buckminster Fuller, one of my early mentors, whom I later went on to work with on several projects during my early career. Another influence at that time were the Case Study Houses, which had an extraordinary glamour to them. They were quite utilitarian, using standard off-the-peg items, but these were being put together to create beautiful architecture.

During the early days of practice, our work on school systems owed a debtto the California SCSD pioneered by Ezra Ehrenkrantz, which was only made possible because he had been in the United Kingdom immediately after the Second World War, when schools were being industrialised.

FM : Back in London, you formed Team 4 with Georgie Wolton, Wendy Cheesman, Su Brumwell and Richard Rogers, and your first projects engaged closely with nature and light, often using brick as a material. But with Reliance Controls – a factory for the electronics industry, and Team 4’s final project – you used standard components such as beams and metal panels, an approach that was closer to that of Ellwood and the Eameses.

NF : There is a very close link between Reliance Controls and the other inspirations that we’ve previously mentioned, such as Craig Ellwood, the Eameses, and in particular the Case Study Houses, with their sparse elegance achieved using materials from catalogues. Reliance Controls marked a transition in the way of looking at a building; it also marked a transition between the practice of Team 4 and the divergent practices that followed. We were all involved in Reliance, but it was particularly close to me. Idid every drawing on that building. If you look at the cut-through section, you can see the various layers and systems within. It was a way of thinking that was quite different from our other buildings. The other projects were more craft-based, although they too were influenced by Serge Chermayeff, Christopher Alexander, Atelier 5, row houses and high density. However, perhaps the project that has the clearest link to the future, both in personal terms and the practice that evolved from it, is the Skybreak House. It is essentially a microcosm, a deep-plan building with generous natural light that focuses on the view. I can certainly link what we did on that project to the work of Foster Associates.

FM: I would like to know about the function of the studio during this period. Because through successive studios we see a kind of development, and more and more they appear as a kind of laboratory where you integrate technologies, and you experiment. Was the studio like a laboratory?

NF: There was interplay between the studio as a creative, experimental workplace and the projects of that time. When we established Foster Associates, we were challen- ging the norm for an architecture studio, which was typically in a Georgian house, shallow and compartmentalised, with small windows and individual offices – the opposite of what we were trying to do. At the time, architects would produce a design and then hand it to an engineer, who would make it stand up. In our studio, we were working in a non-linear way and looking at all the disciplines coming together – the idea of a round table, which still remains at the heart of our work. Around that table, we were simultaneously looking at a project in terms of its structure, its environmental systems and its costing – it was a systems way of thinking. Rather like the buildings that I’ve described, our studios are invariably deep spaces. The Great Portland Street studio was focused on the street, with large windows that broke down the barrier between the public outside and those who are working inside.

FM: The notion of ‘design systems’ accompanies all your work. You used Robert Propst’s Action Office system right from the start – just one way in which you revolutionised the design of office programs. If we refer to the notions of system and integration, what was your understanding of these concepts at the time, and how were they decisive?

NF: I would say that it was the birth of something that has informed everything that we’ve done since. It started way back at the Yale School of Architecture. When presented with a project to design a tall tower, I asked the dean, Paul Rudolph, if I could I work with an engineer. That was heresy – the idea of engaging creatively with an engineer rather than designing as the maestro. For me, that collaborative spirit was liberating and I felt more empowered as an architect. Our studio environment is designed to encourage this way of thinking and break down the barriers between the different disciplines. For example, a structure can be designed in a way that allows you to thread the building services through its voids. That goes against the traditional way of thinking, where you conceive of the structure and then you suspend the ductwork below it. I believe our approach produces buildings that perform better and are more joyful. If I fast-forward to our Apple Park project, the concrete slabs incorporate small bore pipes, which heat and cool them, as well as reinforcing bars which make the building work structurally. The concrete is polished like a rare stone. The end result is not only more beautiful, but a far more compact and environmentally sustainable building.

FM: At a certain point, your interest in systems thinking intersected with similar research by the famous architect Richard Buckminster Fuller. When you met him, you formalised new concepts, including that of the ‘envelope’ – the idea of achieving a maximum volume within a reduced enclosure. This is how the two of you developed the Autonomous House project. How did the notions of environment and system find a new dimension through your collaboration with Buckminster Fuller?

NF: I think the approach that we have developed and evolved – considering the building as an integration of various systems, structural, environmental, and so on – is a built version of Fuller’s philosophy of ‘doing more with less’. You’re certainly correct when you say that he brought a new awareness of volumetric importance. The idea of forms that can enclose the maximum volume with the minimum external wall plays a major role when it comes to sustainability. Foster Associates was born at the same time as the idea of ‘green architecture’, although that phrase was yet to be invented. You had Rachel Carson, who was drawing attention to the impact of pesticides on the planet’s ecosystems in her book Silent Spring. The Apollo astronauts captured that famous image, Earthrise, which made us all aware of the very thin protective layer around the planet. This was picked up by Buckminster Fuller in his book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. You also had Cybernetics by Norbert Wiener, which had a significant impact during that period. Consciously or unconsciously, I think these happenings provided inspiration for a clarity and a level of performance in our architecture.

FM: In the past, you have mentioned your systems approach, in which the constituent entities of a building are broken down into separate systems that, when reassembled, create a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. It’s a way of thinking that relates to the Aristotelian arguments adopted by Norbert Wiener in Cybernetics, as you have mentioned. This holistic understanding is far removed from theories of postmodernism that were around at that time. How did the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Headquarters and London Stansted Airport – two projects that embody ideas and practices that can be found across your work – confirm this holistic approach?

NF: I think the arrival of postmodernism is really when fashion and style subvert design. Our approach, in terms of a building as an integration of systems, was all about interdependencies – you change one thing and it has a knock-on effect. What we were doing was certainly against the tide. At the time, I saw the essence of design not as fashion and style, but as a response to needs. You quoted two examples. In Hong Kong, we challenged the typical office building, taking the traditional central core out, fragmenting it and putting it on the sides of the floor plate. That was a revolution, in the same way that the second example, Stansted Airport, literally turned the model of an airport terminal at the time upside down. The prevailing model was an umbrella of structure, services, mechanical plant on the roof, big ducts moving air, and no natural light. We put all that heavy stuff under the floor and liberated the roof for sunlight and to save energy – to make the terminal a more exciting and beautiful experience. That was achieved through the process of listening, challenging, and then, in that instance, reinventing. It was a revolutionary move that was emulated by many others and became a standard model. Our subsequent aviation projects have been an evolutionary development of this idea rather than revolutionary, but are equally honourable.

FM: You have often been associated with the high-tech movement. It’s an idea that you have dismissed, stating your preference for a more structural vision, in which architecture corresponds to the more measured ‘skin and bones’ principle evoked by Mies van der Rohe. The technology must be adapted and eventually, through its efficiency, gradually fade away, in keeping with the idea of ‘ephemeralisation’ put forward by Buckminster Fuller. How would you define your conception of technology?

NF: I think that technology is a means to social ends – to lift the spirits and protect you from the elements. In other words, not just to be comfortable but to create a lifestyle – something which is about delight. What you’re describing as ephemeralisation is a means to that end. It’s really dissolving the structure and the services, integrating them so that they visually evaporate. If you look at the Centre Pompidou by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, it makes a celebration of its services – you can see those service and structural elements on the outside. If you look at our Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, from the same period, you have a structure and all the services integrated into it. So, the structure is designed for the environmental performance, as well as the structural performance. The aim was to create a building which is healthy and breathing. I would say it is a personal approach, born out of the systems theory which was applied in other spheres at that time. Although my approach has evolved, the idea of ephemeralisation remains a constant to this day. |

|

|

| Soren Larson, "Pritzker winner Sir Norman Foster mixes technology with humanism", Architectural record 5/1999, "Record News" p. 95 |

|

|

|

|

|

EXHIBITIONS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Norman Foster, Paris [France], Centre Pompidou (Galerie 1, level 6), 10 may / 7 august 2023

Covering nearly two thousand two hundred square metres, the Centre Pompidou’s retrospective exhibition dedicated to Norman Foster in Galerie 1 reviews the different periods in the architect’s work and highlights his cutting-edge creations, such as the headquarters of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (Hong Kong, 1979-1986), the Carré d’Art (Nîmes, 1984-1993), Hong Kong International Airport (1992-1998) and Apple Park (Cupertino, United States, 2009-2017). Covering nearly two thousand two hundred square metres, the Centre Pompidou’s retrospective exhibition dedicated to Norman Foster in Galerie 1 reviews the different periods in the architect’s work and highlights his cutting-edge creations, such as the headquarters of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (Hong Kong, 1979-1986), the Carré d’Art (Nîmes, 1984-1993), Hong Kong International Airport (1992-1998) and Apple Park (Cupertino, United States, 2009-2017).

The scenography of the exhibition was designed by Norman Foster and executed in collaboration with Foster + Partners and the Norman Foster Foundation.

The layout unfolds in the course of seven themes, Nature and Urbanity; Skin and Bones; Vertical City; History and Tradition; Planning and Place; Networks and Mobility and Future. Drawings, sketches, original scale models and dioramas, along with many videos, enable visitors to discover around 130 major projects. Welcoming visitors at the entrance to the exhibition, a drawing gallery showcases items never seen before in France, consisting of drawings, sketchbooks, sketches and photographs taken by the architect. The layout unfolds in the course of seven themes, Nature and Urbanity; Skin and Bones; Vertical City; History and Tradition; Planning and Place; Networks and Mobility and Future. Drawings, sketches, original scale models and dioramas, along with many videos, enable visitors to discover around 130 major projects. Welcoming visitors at the entrance to the exhibition, a drawing gallery showcases items never seen before in France, consisting of drawings, sketchbooks, sketches and photographs taken by the architect.

Because they constitute Norman Foster's sources of inspiration and resonate with his architecture, works by Fernand Léger, Constantin Brancusi, Umberto Boccioni and Ai Wei Wei are also presented in the exhibition, along with industrial creations, a glider and automobiles.

Any encounter with the work of architect Norman Foster immediately conjures up what seems to be his most striking projects, those that are synonymous with the image of a city, a region or, more simply, have changed the shape of a site or the configuration of a location or a square.

Large airports, transport networks, tall buildings, the headquarters of large companies, public buildings, major structures, urban development programmes, museums... with several hundred projects studied or completed throughout the world, Norman Foster has engaged with the full complexity of the organisation of great industrial societies.

The Centre Pompidou dedicates a major retrospective exhibition to the British architect in the very building that was among the first manifestations of the " High Tech " architectural trend of which Norman Foster is considered to be a leader. Foster founded the Team 4 agency in London in 1963 with Wendy Cheesman and Richard Rogers who, along with Renzo Piano, would be the architect of the Centre Pompidou in 1977. In 1967 Foster founded his Foster Associates practice, which became Foster and Partners in 1992.

Norman Foster imposed the image of a practice that has preserved its identity as a global agency always open to research and innovation, and which integrates all technical, economic, social and environmental dimensions in its projects. A broader understanding of the concept of environment as including nature and the whole biosphere is a central preoccupation in his work. He identifies high technology with a technosphere that monitors the destructive effects of the industrial world with an economy that is compatible with life on earth.

This global concept combining the deployment of technologies with a comprehension of the concept of environment is founded on the work of Richard Buckminster Fuller, the American architect with whom Foster worked on various projects. Thus, as early as the 1960s and 1970s, at a time when industrial society was waking up to environmental challenges, Norman Foster participated in the emergence of the ecological movement and its development in the course of more contemporary projects.

Organisation of the exhibition

Texts from Norman Foster

Drawing gallery

Sketching and drawing has been a way of life for as long as I can remember. Someone said that, if you ask me a question, then I will do you a sketch. The spontaneous concept sketch, which might seem like a blinding flash of inspiration, is most likely borne out of a total immersion in the many issues. For me, design starts with a sketch, continuing as a tool of communication through the long process that follows in the studio, factories and finally onto the building site. The drawing is a more premeditated exercise and the cutaway sectional perspective, along with three dimensional details that I favour, have their links to past influences. In 1975 I started the habit of carrying an A4 notebook for sketching and writing – a selection of these are displayed in the central cabinets, surrounded by walls devoted to personal drawings. A further cabinet contains back-lit transparencies which I have captured with a camera and they chart some of the diverse design influences over time.

Nature and urbanity Nature and urbanity

These are two parallel worlds which intersect creatively. We can preserve nature by building dense urban clusters, with privacy ensured by design – the opposite of unsustainable urban sprawl. We can blend with the landscape by digging into it or leaving it undisturbed, by touching the ground lightly. By bringing nature into our cities and buildings we can humanise spaces with greenery, views, fresh air and natural light – more healthy, joyful and consuming less energy. The tree is a metaphor for the ideal building. It breathes and responds to changes in the seasons. It is inspirational as a cantilevered structure in harmony with nature. As a self-sustaining ecosystem, it harvests water and solar energy, recycles waste and absorbs carbon dioxide. These design principles date back to the nineteen sixties. However, in the last decade they have been scientifically proved to create environments which, compared to conventional practice, are more healthy and with improved levels of human performance. What is good for our spirit can also be good for the environment.

Skin and bones Skin and bones

It was an eminent critic who observed that all of our projects could be categorised as either skin or bones depending on whether the dominant external expression was of the smooth façade – the skin – or the skeleton of a supporting structure. This figurative expression is not arbitrary, rather it is the outcome of considering, in each case, the relationship between the separate systems of structure, environmental services and external cladding. The selection of projects to illustrate this theme is random - and from all of the other categories. There are parallels between architecture, art and design. In a medieval cathedral, the structure is the architecture,and the architecture is the structure, as in several of our towers. Links can be drawn with the white gridded structures of Sol LeWitt, and Fernand Léger’s construction workers in their network of iron girders. The smooth aerodynamics of our skin projects resonate with the streamlined forms of automobiles and sculptures by Boccioni and Brancusi, and bear comparisons with the world of aviation – the streamlined fabric of airships or the white composites of high performance sailplanes.

The vertical city

The skyscraper is emblematic of the modern age city and is a reminder that the city is arguably civilisation’s greatest invention. A vertical community, well served by public transport, can be a model of sustainability especially when compared with a sprawling low rise equivalent in a car dependent suburb. Our own design history of towers is one of challenging convention. We were the first to question the traditional tower, with its central core of mechanical plant, circulation and structure, and instead to create open, stacked spaces, flexible for change and with see-through views. Here, the ancillary services were grouped alongside the working or living spaces. This led to a further evolution with the first ever series of ‘breathing’ towers. In the quest to reduce energy consumption and create a healthier and more desirable lifestyle, we showed that a system of natural ventilation, moving large volumes of fresh filtered air, could be part of a controlled internal climate. My tower design in the Yale Master Class was prophetic in its elimination of the central core.

History and tradition History and tradition

It has been said that if you want to look far ahead to the future, first look far back to in time. This advice applies to many of our historic projects where the designs are rooted in a study of the past. Recycling an existing building, particularly one of civic importance, is far more sustainable than building afresh. Historic structures are typically marked by layers of growth – each of its own period – and our approach has been to continue that pattern with a respectful imprint of today, rather than a pastiche of the past. Tradition in architecture overlaps with history and for me it is the vernacular or indigenous tradition – once described as Architecture Without Architects. It fascinated me as a student and led me to measure and draw a medieval barn and windmill. The vernacular continues to inspire me as a design influence – not only in its forms but in the use of materials and the environmental lessons of cooling and heating before an age of cheap energy.

Planning and places

Placemaking is related to the world of urban spaces – it is the infrastructure of streets, plazas, parks, bridges and connections – the urban glue that binds together the individual buildings and determines the DNA or identity of a town or city. Place is also the spirit, even if not spiritual by its origins. Infrastructure is at the heart of masterplanning and can generate, transform or reinvent a city or region. It can respond to crises from which, historically, cities have always emerged stronger. It can encourage the community of neighbourhoods and, by urban design interventions, show how small changes can deliver major environmental gains. Masterplanning can encourage the compact, sustainable, walkable and equitable city. It can bring nature and biodiver- sity, whether as a protective green belt, in parks, avenues of trees or dispersed through the urban fabric to beautify and to clean the air we breathe. As a student I analysed and documented some of the great European squares. Then, as now, I am as fascinated by the architecture of urban places, the outdoor rooms, as I am by the architecture of individual buildings.

Networks and mobility Networks and mobility

Mobility of people, goods and information needs physical infrastructure, whether down on earth, aloft in space or on another planet. The growth in air travel, alongside high-speed rail networks, has provided us with the opportunity to reinvent the international terminal – to elevate it as the gateway to a nation, with all the attendant symbolism – to open it up to the sky for delight as well as savings of energy and maintenance. Bridges that connect riverbanks or plateaus in the landscape also have an heroic and symbolic dimension, and have led us to structural innovation in the pursuit of visual lightness and identity of place. Even the digital world needs to come down to earth in the transmission tower which offers similar scope for reinvention.

Futures Futures

Futures overlaps with Networks and Mobility but is projected ahead in time and space. It anticipates a more autonomous world where clean energy sources are abundantly available – free from transmission grids and mega power stations. The Norman Foster Foundation is working on this concept with MIT’s Centre for Advanced Nuclear Energy Systems. A similar trend is apparent in mobility with autonomous self-driving systems. There are parallels with the recent revolution in telecommunications as satellites and handheld devices have replaced telephone exchanges and endless poles and cables in the landscape. Working with the European Space Agency and NASA, we have explored Lunar and Martian habitations. The dome-like structures have visual similarities with the system of droneports that we proposed for rural Africa – both use the earth of their locality as prime construction materials and all, literally, grow out of their sites. The science fiction fantasies and inspirations of my youth are the project realities of today. |

|

|

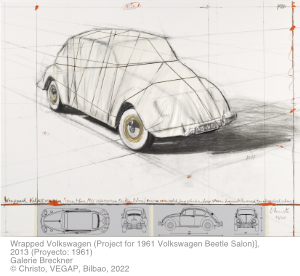

Norman Foster Norman Foster (concept and design), Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture, Bilbao (Spain), Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 8 april / 18 september 2022

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao presents Motion. Autos, Art, Architecture, sponsored by Iberdrola and Volkswagen Group. The exhibition celebrates the artistic dimension of the automobile and links it to the parallel worlds of painting, sculpture, architecture, photography, and film. Taking a holistic approach, the exhibition challenges the separate silos of these disciplines and explores how they are visually and culturally linked.

The exhibition considers the affinities between technology and art, showing for example how use of the wind tunnel helped to aerodynamically shape the automobile to go faster with more economic use of power. This streamlining revolution was echoed in works of the Futurist movement and by other artists of the period. It was also reflected in the industrial design of everything from household appliances to locomotives. The exhibition brings together around forty automobiles – each the best of its kind in such terms as beauty, rarity, technical progress and a vision of the future. These are placed centre stage in the galleries and surrounded by significant works of art and architecture. Many of these have never before left their homes in private collections and public institutions, and as such, are being presented to a wider audience for the first time. The exhibition considers the affinities between technology and art, showing for example how use of the wind tunnel helped to aerodynamically shape the automobile to go faster with more economic use of power. This streamlining revolution was echoed in works of the Futurist movement and by other artists of the period. It was also reflected in the industrial design of everything from household appliances to locomotives. The exhibition brings together around forty automobiles – each the best of its kind in such terms as beauty, rarity, technical progress and a vision of the future. These are placed centre stage in the galleries and surrounded by significant works of art and architecture. Many of these have never before left their homes in private collections and public institutions, and as such, are being presented to a wider audience for the first time.

The exhibition is spread over ten spaces in the museum. Each of seven galleries is themed in a roughly chronological order. These start with Beginnings and continue as Sculptures, Popularising, Sporting, Visionaries and Americana and close with a gallery dedicated to what the future of mobility may hold.

Future shows the work of a younger generation of students from sixteen schools of design and architecture on four continents, who were invited by the Norman Foster Foundation to imagine what mobility might be at the end of the century, coinciding roughly with the 200th anniversary of the birth of the automobile. Future shows the work of a younger generation of students from sixteen schools of design and architecture on four continents, who were invited by the Norman Foster Foundation to imagine what mobility might be at the end of the century, coinciding roughly with the 200th anniversary of the birth of the automobile.

The remaining four spaces comprise a corridor containing a timeline and immersive sound experience, a live clay-modelling studio and an area devoted to models.

Unlike any other single invention, the automobile has completely transformed the urban and rural landscape of our planet and in turn our lifestyle. We are on the edge of a new revolution of electric power, so this exhibition could be seen as a requiem for the last days of combustion. |

|

|

| City Visions: A Sustainable Future, Wuhan (China), Big House, 8 may / 15 june 2017 |

|

|

Craft + Manufacture: Industrial Design by Foster + Partners, London, The Aram Gallery, 12 may / 2 july 2016

|

|

|

| Foster + Partners: Architecture, Urbanism, Innovation, Tokyo, Mori Art Museum, 1 january / 14 february 2016 |

|

|

| The Brits Who Built the Modern World. 1950-2012, London, RIBA’s new Architecture Gallery, 13 february / 27 may 2014 |

|

|

Moving. Norman Foster on Art, Nîmes, Carré d'Art. Nîmes Museum of Contemporary Art, 3 may / 15 september 2013 [ » images ] Moving. Norman Foster on Art, Nîmes, Carré d'Art. Nîmes Museum of Contemporary Art, 3 may / 15 september 2013 [ » images ] |

|

|

| Norman Foster (ed.), Gateway, Venezia, Arsenale, 29 august / 25 november 2012 [ » read more ] |

|

|

| Architecting the Future: Buckminster Fuller & Norman Foster, Miami, Miami Design District, 29 november / 4 december 2011 |

|

|

The Art of Architecture: Foster + Partners The Art of Architecture: Foster + Partners

Dallas, Nasher Sculpture Center, 26 september 2009 / 10 january 2010

Hong Kong, Hong Kong Arts Centre, 27 august / 22 september 2011

Shanghai, Shanghai Oil Painting and Sculpture Institute, 25 july / 25 august 2012

Kuala Lumpur, Galeri Petronas, 7 march / 12 may 2013

Bangkok, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC), 4 april / 29 june 2014 |

|

|

| Norman Foster Dibujos. 1958-2008, Madrid, Ivorypress, 1 / 19 september 2009 |

|

|

Foster + Partners. Working with history

München, Lenbachhaus Museum, 21 october / 22 february 2009

København [Copenhagen], DAC - Danish Architecture Centr, 19 june / 30 august 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

ADDITIONS AND DIGRESSIONS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|